Practice Review: Peoplehood

A Protestant Reformation of psychiatry is under way. Coaches are freeing CBT and positive psychology from the bounds of the clinic. Self-diagnosing groups are challenging the authority of psychiatrists to gate-keep diagnosis, forming their own connection to the cultural labels of ADHD, autism spectrum, and BPD. Therapists themselves are going direct-to-consumer with the practices they’ve learned. The major theme of these trends is that consumers, not service providers, now drive which mental health and emotional wellness practices are adopted. Choice of treatment modality is increasingly a choice of cultural tribe.

Along with this shift in psychiatric practice, new forms of social care are burgeoning. Group therapies have been out of fashion for a few decades, but other group modalities that do away with clinical idiom are on the rise. From social saunas and bath houses to new types of retreat, these spaces freely blend psychological treatments with physiological health services and spiritual enrichment. Of these new social wellness spaces, one might say that everything is downstream of Esalen.

The direct-to-consumer phenomenon means that unlicensed professionals may now play in the same regions of the soul that the psychiatric establishment monopolized in the 20th century. But in the same stroke, new opportunities abound for psychologists to involve themselves with non-clinical healing and growth practices. As with the Reformation, the boundaries of the sacred and secular are being redrawn. For better or for worse, credentials are being de-emphasized, while quality of practice and practitioner is of utmost importance. As “medical” and “scientific” and “spiritual” idioms merge and cross over, tools both new and old will be needed to sculpt these spaces, to understand what works and what doesn’t, what is safe and what puts clients at risk. We’ll need to closely examine new church-like spaces and “care cultures” to learn from them and critically evaluate what they are getting right and wrong.

In these Practice Reviews, we look at spaces and practices that are defining the new landscape of emotional and social well-being.

Overview

In this Practice Review we’ll look at Peoplehood, a group dialogue space created by the founders of Soulcycle. I will always share any incentives when reviewing practices; in this case, I paid out of pocket for every Peoplehood session I tried.

The structure of a typical Gather is as follows:

OPENING

- Arrival and getting seated

- Opening breathwork

- Intros - going around in a circle answering an icebreaker question

CORE

- Introduction of the day’s theme

- 3 minute journaling exercise on the theme with pen + paper

- Second 3-minute journaling exercise on a second question

- “Higher listening” exchange with a partner

- Second “higher listening” conversation or exchange

- Return to group for sharing

CLOSING

- Closing sermon and outro breathwork

- Exit to lobby

Opening

For me, Peoplehood is emblematic of the cultural shift from DTC brands to DTC practices and protocols. In my 2022 essay on this shift, Life After Lifestyle, Peoplehood was already an example. It is one of the more well-known hybrid social wellness spaces, having received several generous writeups in East Coast prestige news media. I’ve known about Peoplehood for some time, but I waited until this year to try it out personally. This spring, the time feels right. I book myself a 4 session package.

My first Peoplehood session, called a Gather, is in the middle of the day on a Friday, a bit of an awkward time for a social practice. I vaguely know what to expect from the prior reading I have done. I am also carrying with me my experiences of other group modalities, including my three years in psychodynamic group therapy with well-known group leader Patti Cox, and several other group dialogue modalities I’ve tried out.

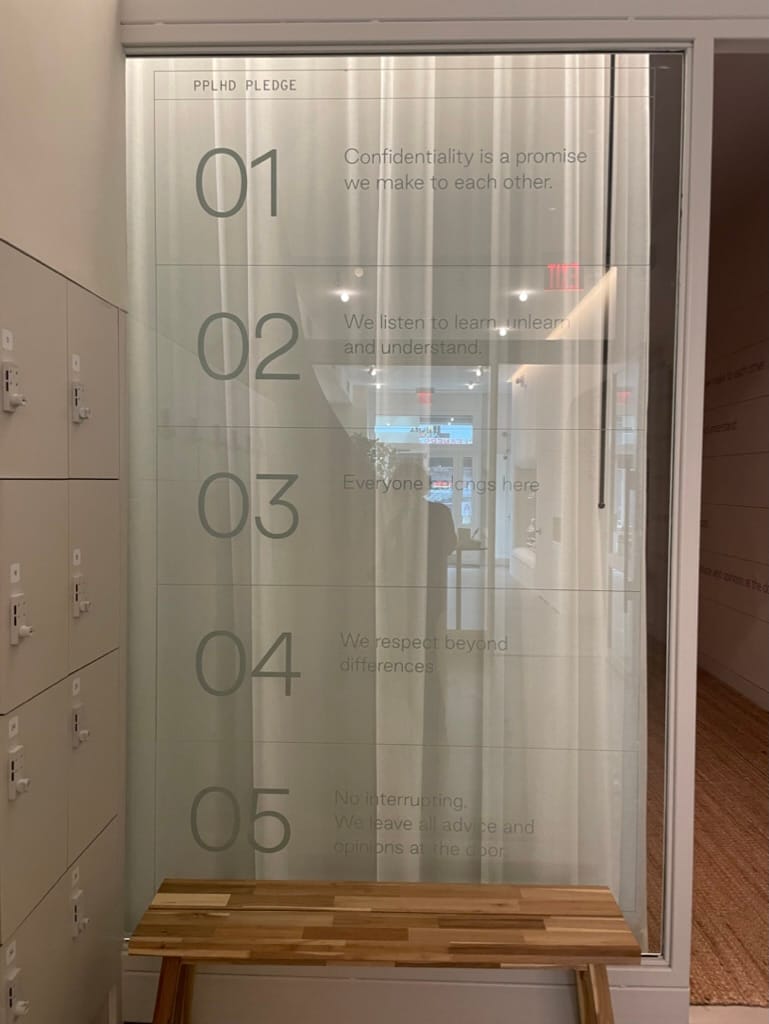

I arrive at Peoplehood’s Chelsea offices and am greeted by a cheerful young woman. She starts a conversation with me easily, telling me that she is studying to be a social worker and is in the second year of her degree. She says that there will only be four people at today’s Gather, and that she will join as one of them. I decline her offer of coffee and go put my things into a combination locker. The interior style of Peoplehood is white and tan, with large text printed on the wall, serving as a reminder that Peoplehood is created by the founders of Soulcycle. It is tasteful but bland. I return to the coffee counter and accept a sparkling water, grateful for the free drinks. I’m still confused as to who will lead our Gather today, until a bouncy small woman in Air Jordans opens the door. This is Gab. Her vibe and attitude are unmistakeably that of an Angeleno.

Only the three of us are here—me and two Peoplehood employees—but it’s time to begin, so we move through the locker hallway into a large, high-ceilinged back room, the floor entirely carpeted by a thick-woven hemp rug. Four chairs surround a low table, on which burns an enormous black candle; it smells good, if slightly weedy. On the sides and corners of the room are several clusters of floor pillows. I’m instructed which chair to sit in. Finally, another woman hurries in the door. She’s in her late 30s and classically New York. Fit, made up, beautiful but somewhat severe-looking, probably an executive. Her left hand is ringless. She immediately reminds me of someone I knew from my group therapy days.

The Gather begins. We start with some guided breathwork. It’s simple box breathing: 4 in, 4 hold, 4 out, 4 hold. Our breathing is soundtracked by not-too-upbeat pop music, something like one song worth of Ed Sheeran. The music is controlled by an iPad in Gab’s hand, which also controls the lights. After a few minutes the breathwork ends and we have “arrived” at the session. Gab turns down the music, but it will continue playing gently in the background the entire time. The scene is now set.

Core

The emerging class of hybrid wellness, healing, and church spaces are oriented toward emotional or relational outcomes. The event flow, facilitation, selection of participants, and above all the practices selected, all lead toward kinds of emotional experiences. Some are what social theorist Joe Edelman calls funnels: social designs that drive participants towards the same goals. This is not to say that all these events and spaces are of an entirely instrumental character, designed to elicit only one kind of emotion. Others are spaces where relational exploration can happen. Yet the flavor of exploration differs dramatically from space to space. Peoplehood is more of an exploratory space, where the overall structure of exploration is listening and hearing.

Each Gather sticks to a guiding theme, such as “habits,” “self-love,” or “people-pleasing.” The theme sets the ground for specific journaling exercises and conversation topics, which form the core of Peoplehood’s experience design. Most Peoplehood Gathers begin with a journaling prompt on the theme. Participants are given a pen and a small card with just enough space to write for 3 minutes. Then the Gather moves into its main exercise: Higher Listening.

The Higher Listening practice is designed to bring participants into the present, where they can have a more honest form of speech with themselves and with others. In this practice, one person speaks while the other listens. Higher Listening is not Carl Rogers-style active listening; the listener does not make experience-affirming comments or ask questions. Listeners are simply instructed to offer 3 uninterrupted minutes of attentive presence, nodding along while their partner speaks their mind and heart on the day’s thematic question. Listeners are only allowed one query —“is there more?”—a suggestion familiar to psychologists prompting their patients for more words. Then partners switch, and the speaker becomes the listener. Interspersed with these conversations are miniature journaling exercises, in which participants further develop their reflections on the theme, and group shares back to the circle.

Let’s examine this flow.

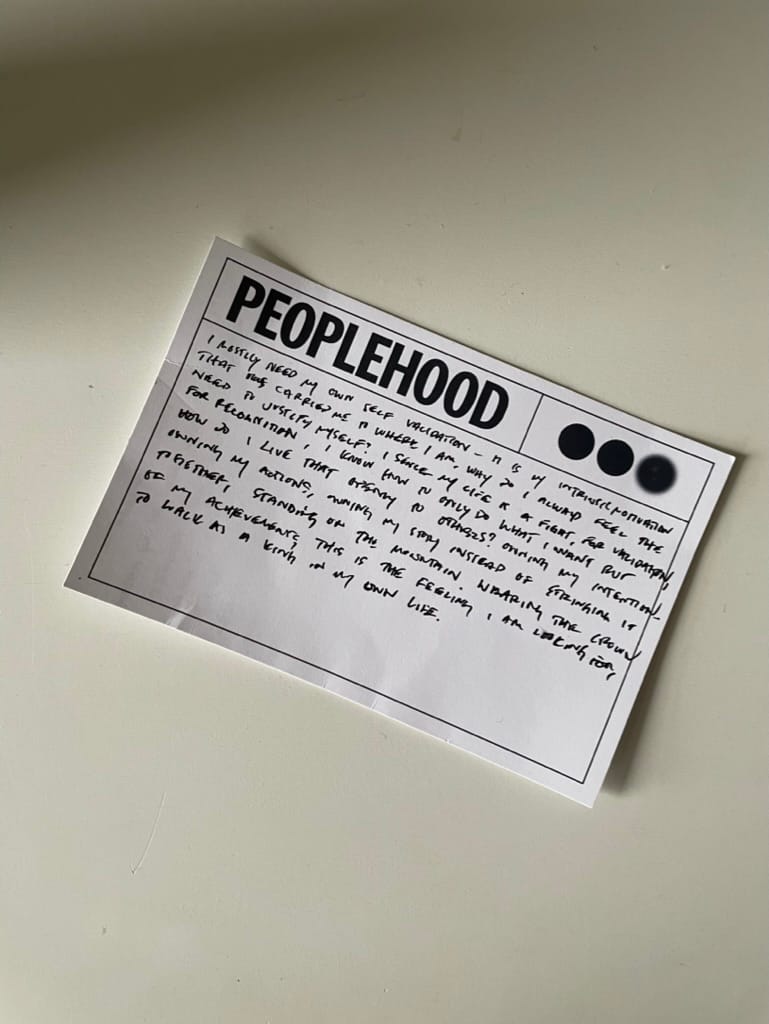

In my first Gather, we introduce ourselves in a round, and answer a question to get in the mood: how are we really doing? This is one of a few questions that Peoplehood reliably uses to open people up. Next, Gab introduces the theme of validation. We all reach for a card and a felt pen from the table, and begin by journaling on this topic. I immediately know what I want to think about: I’ve been reflecting on the way I fail to stand up for my own achievements. Sometimes I feel like I’m fighting for recognition, that I’m expecting not to get it—I write down that the validation I most need is my own.

After a few minutes of quiet writing, Gab calls our attention back and briefly explains the higher listening exercise. She pairs me up with the young woman who let me in the door, while she takes the high-strung executive. We get up from our chairs and transition to the floor pillows bordering the room, adjusting them until we’re comfortable. I let my interlocuter speak first. Peoplehood practices Chatham House Rules, so I won’t share her words here, but I listen carefully, looking into her eyes and nodding on as she speaks. I don’t need to prompt for more; she’s practiced at talking the whole way through. When it’s my turn to share—Gab calls over and tells us it’s time—I begin to talk about my reflections on speaking more easily about my accomplishments. It isn’t the first time I’ve spoken about this to someone, and I don’t make any new progress. In three minutes, I feel I can’t explain all of it. But my partner nods and gazes at me attentively. I feel listened to, but not quite heard.

We’re now called back for another round of journaling. I notice for the second time that I don’t have a great place to put my card, and that most people are awkwardly writing with their knees as a surface. I choose to sit on the floor and use the coffee table instead. A second round of conversation follows, and this time I pair with Gab. I’m disappointed that I wasn’t paired with the executive; for some reason I’m drawn to her. I feel in a vague way that I could be helpful to her.

Closing

Whatever is “opened” must be “closed.” A skillful facilitator’s job is to conclude an experience in a way that feels resolved and adequately finished. The concept of the “container,” which is not indigenous to academic psychology or psychoanalytic discourse, is one useful term which has been adopted by group practitioners of all stripes to explain how a space is facilitated from start to finish. Closure of these pseudo-church relational spaces has two inevitable components: group sharing and what I call a closing sermon.

The group share serves two functions: first, it re-establishes “us-ness” after whatever inner work has just happened in the space. In the case of Peoplehood, participants have done both solo journaling and paired conversations, and may have gone into themselves so to speak, may have entered their own inner world of thought and emotion. Sharing back to the group puts them again in the mode of relating to others, re-forming a group connection which allows the facilitator to end the experience for everyone at once. Secondly, group shares serve as a way for facilitators to get feedback on what has happened in the group. The feedback can help the facilitator learn what effects their group management style had, and it also serves the business goals. Sharebacks reliably generate the sort of speech that end up as customer testimonials on websites.

The sermon, an indispensable part of these spaces and experiences, deserves a piece of its own. Although many facilitators would disclaim the term, there is an undeniable preacherliness to the delivery. To formally end a space, one has to stand above, to preside over the group and take momentary authority. This requires a certain affect, a style of rhetoric, and a capacity to offer guiding words that smoothly reflect many of the themes that were alive in the group space. Peoplehood is no exception here. Before or after the closing round of box breathwork, guides are expected to offer an impromptu reflection on the session’s theme and whatever came up in the session. Even as they are only a minute long, offered with everyone’s eyes closed, the prayerful quality is palpable.

Then second round of Higher Listening ends, and we are called back to the circle for sharing reflections and experiences. Is there anything we’d like to say to the group before we end? I often feel that commercial social wellness spaces enter into the sharing part of the meeting too abruptly, and the sudden shift toward closure jars me at Peoplehood as well. Back in our chairs, we go around in a circle. Nobody has anything particularly memorable to say. For my share, however, I mention that I wish I had the opportunity to speak with the executive woman. She seems surprised, but her face lights up and she responds warmly that it would have been nice to speak to me too.

Finally, Gab asks us to close our eyes. As I do, I notice the subtle background music has become more audible. Gab begins a bit of a closing talk. Her remarks are unplanned, and with her eyes closed as well, she rambles for about two minutes on the theme of validation and giving ourselves—love, grace, acceptance, something or other—and how the space and community at Peoplehood can provide that. I find myself a bit let down by this, as I was hoping for a slightly more stirring conclusion. Throughout the session, Gab has done a lot of “telling” about the work done at Peoplehood, rather than “showing.” We do one more round of box breathwork, and finish. There are no further instructions, but Gab and the other Peoplehood part-timer get up from their chairs, raise the lights and open the door. I follow suit.

I wander slowly into the lobby, grabbing my stuff from the lockers on the way. I’m a bit lost as to what to do. I didn’t feel entirely satisfied by the end of the experience, and find myself wanting to chat more. I start conversing again with the part-time employee, who once again offers me coffee. I decline politely and try to ask her about her social work courseload. The conversation doesn’t really go anywhere, so I just ask for where I should get lunch in the area; she recommends me a spot, and I head there to think about my experience.

Online Gathers

Before the critical assessment, I want to cover Peoplehood’s online Gather experience. I’m not a fan of online group experiences in general, but they are so common now, and so palpably distinct from in-person spaces, that they deserve a brief analysis of their own.

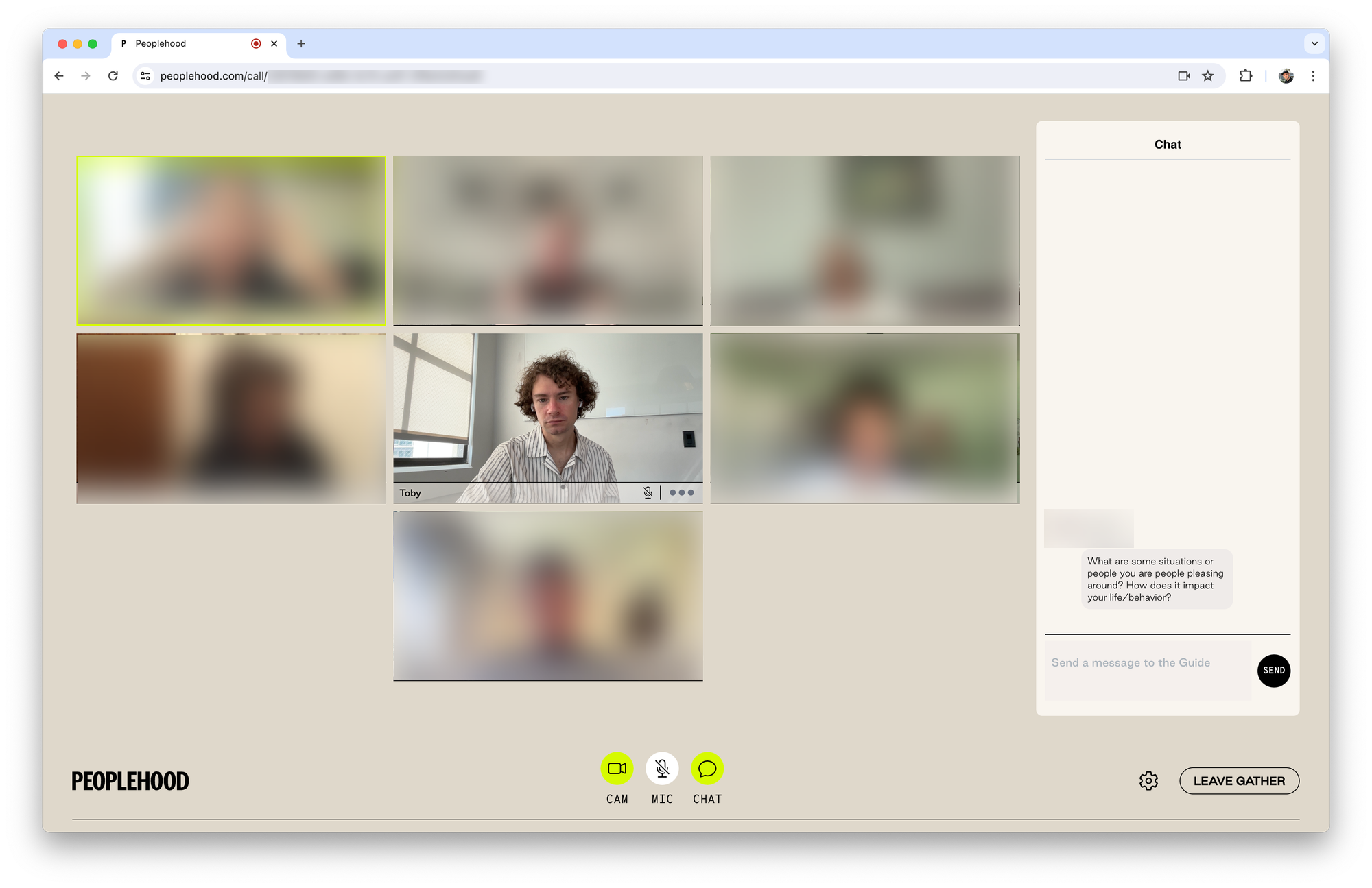

The virtual Peoplehood happens through a slickly customized video portal. Music plays the whole time here too, and the guide is responsible for controlling it as well as the breakout rooms. Instead of a few people in the room in the West Village, between eight and twenty show up from all over. A few are clearly regulars, which is interesting to see.

The facilitator at my first online Gather is the best guide I’ve had at Peoplehood. Crunched into one small box on a screen full of people, Anthony exaggerates his hand gestures and body movements to let people know they are heard and felt. Even on the screen his warmth and genuine skill show through. I’m impressed. This is the true meaning of emotional labor: Anthony has to do much of the feeling work on behalf of the group. I feel this strongly after one group share, where he says something to the effect of wanting to sit with what all that has just been said. He doesn’t want to move on directly; he wants to let it breathe. In person, when strong themes and feelings arise in a group they can energetically fill the space, intimately acknowledged by participants, or taken up by a facilitator who can bring everyone to a shared awareness. On a video screen, spacious circulation of feelings is much harder to achieve. Besides, the clock is ticking: Gathers are only an hour long, and Anthony has to put us into paired breakout rooms for Higher Listening.

It’s a similar flow to the in-person Gather experience, a back-and-forth between journaling, conversation, an interlude of commentary by the facilitator, and group sharing. In one online Gather, the theme is “people-pleasing,” and I share conversations with others about moments we acted in order to please others, as well as moments we intentionally broke with conformity. The online format seems to be adjusted for less journaling and more group sharing.

The video-based Gather feels less substantial than the in-person one, but as it winds down, I am surprised to find myself feeling pretty good. It’s the end of the day, and I feel more warm and relaxed than I did before we started. My interactions have not been satisfying, but I feel less frustrated than in the IRL event. The call ends and I reflect on why. Is this because of the screen was full of smiles at the end? Or is it because of the genuine effort and feeling of the facilitator? Because my expectations for online calls are just lower?

Later on, I land on two reasons I felt this way. Firstly, Anthony managed to hold space well, doing so much of the group’s feeling work; I experienced and appreciated his warmth. Secondly, I think there’s something about the digital medium. The flow and activities were the same, but being a glorified Zoom meeting makes it a different format altogether. Most video calls are work meetings. To have a somewhat open-hearted interaction over video is certainly a novelty, and an improvement over what I normally do on a screen. This alone might account for my positive feelings.

Critical Review

After reading through this description of a tightly scripted social interaction, one might ask: why bother with any of it? Why can’t you just go to a bar, say hello to whosoever is drinking a whisky soda next to you, and rant to each other about the big and little miseries of life? Even if “higher listening” isn’t engaged, wouldn’t it feel more natural? This kind of idealized social interaction does happen, but it requires a lot of social courage. The local bar, the library, and the yoga studio don’t go out of their way to facilitate these kinds of connections.

Peoplehood, on the other hand, does. It’s just one of many social enterprises responding to what I call the loneliness apparatus: the set of institutions and incentives around the public health message of a social isolation epidemic. Where other semipublic urban gathering spaces fail to create lasting social bonds, Peoplehood and its generation of social wellness businesses are trying to build spaces for intentional connection. The question is how successful they are is at doing so. Exploratory spaces rather than goal-oriented funnels tend to be better at fostering connection between people. But at Peoplehood, neutered exploration is a recurring theme.

Gathers provide little opportunity to work on the challenges I bring up, or even explore anyone else’s personality. I can bring up an issue I have, but because of the “Higher Listening” listening format, I know I won’t get the chance to explore in depth how another person relates to that issue in their life. “Higher Listening” is actually one-sided. Without being asked questions, speaking just feels like dumping on someone. What’s the point of doing that if they aren’t going to respond, empathize, make you feel heard? In my second Gather, I forced myself to say something truly vulnerable about a habit I wanted to break. Before I spoke, I found myself wondering: why should I expose myself in this way at all? Why should I be vulnerable about this embarrassing thing that I know I won’t get any meaningful feedback or empathy about? All I know I’ll get is some knowing nods from my listening partner, and indeed, that’s all I got. I didn’t feel judged by him, but nor did I feel understood. I don’t know if I’m glad I opened up about that thing to a stranger. Listening in this open way does created a temporary bond between speaker and listener. But when the second person’s turn to talk comes, that bond is not strengthened. It’s a missed opportunity for true connection.

On the other hand, the listening itself is not carried to its fullest potential. Higher Listening is a sort of foreclosed version of how therapists listen: relaxed, present, sensitive to sensations and emotional experiences that arise. One can learn to do this full-body listening, to notice energy and hold and comment on it. But this takes time and training. The potential for this practice is there in Peoplehood, but it is not developed.

This is not the only way in which Peoplehood ignores what it could learn from existing modalities and practices. 70s-style encounter groups, T-groups, and authentic relating exercises are not hard to find and learn about. When I asked employees if they had ever tried circling, they had never even heard of it. It was surprising to me that the staff hadn’t even experienced or trained in other group facilitation and dialogue exercises. Studying these practices could improve the format, and would strengthen Peoplehood’s relationship with a long tradition of group work. In Molly Longman’s piece on Peoplehood, founder Julie Rice was quoted to say that “she and [cofounder] Cutler had spent three years perfecting the Gathers, incorporating research and lessons from AA groups and different religions.” This was a surprise to me, given that in my four Gathers no reference to any faith community was made. Moreover, Peoplehood staff keep reiterating that a Gather is some sort of new thing that can’t be defined. This is another missed opportunity: if Gathers carried the weight of any existing tradition, whether psychological or spiritual, they wouldn’t feel so terribly impotent.

On the other hand, irrelevant references are frequently deployed without reason. Two different guides brought up the “morning pages” exercise from the book The Artist’s Way when explaining how to journal and to speak without stopping in the Higher Listening exercise. The references were totally lost on most people; when simply saying “free writing” or “just keep talking” would have sufficed. The fact that this unhelpful comparison is baked into the training, rather than mentioning of any other group modality, demonstrates how the novelty of the Gather is greatly overestimated by its designers.

The main question I would put to Peoplehood is: what is it trying to do? Social groups can be goal-less yet are still organized around many different principles. Community, connection, self-knowledge, learning, surprise, shock, exhilaration, are all valid principles. But Peoplehood is not coherently structured around any one of these. For instance: the 3-minute sharing exercises opens the door to intimacy. But pairs are prevented from walking through it because of the way the stilted format blocks conversations from developing. This is the reason people tend to hover in the lobby after Gathers—they are craving to continue with real connection. The whole experience could be made better if everyone went to a bar afterward. Tongues would be loosened and vulnerable conversation would flow. This outcome is possible to recreate within the Gather container, but Peoplehood has not done it. And the same can be said about any other principle. I’ve participated in many types of circle-based dialogue practice. Some were more challenging or less tightly facilitated, but all left me more satisfied or emotionally raw or activated than the Gathers do.

If Peoplehood Gathers were 90 minutes long instead of 60, their tepidness would be much more obvious. As is, the overall Gather flow is sensible but rushed, so as to make one ask “what exactly did I just experience?" instead of noticing that nothing much happens. Online the format is even more cramped. This gets to issues of economy where social wellness spaces are concerned. The Peoplehood experience wants to economize on time, so it cuts out all the parts of emotional process that allow for people to grow. What’s missing is not a “peak experience,” but the feeling of something, anything at all actually happening.

I think this nothingburger feeling comes chiefly from the fact that the social design has eliminated risk. Bonding with others requires risk; risk requires greater intention setting, more opinionated facilitation, and stronger boundaries. Gathers, conversely, are designed to be walk-in experiences. Risk is also inherent in any relationship that exists over time. Gathers, conversely, kick you out after a session with no encouragement to connect with others you may have had a spark of connection with.

In the New York Times’ 2022 coverage of Peoplehood, psychologists and sociologists weigh in on the potential risks of “putting your spiritual, psychological and emotional health in the hands of someone trying to build and scale a giant business.” However justified these fears are, they are rather wasted on Peoplehood.

Peoplehood is just a taste of what’s to come: what we will be examining at Care Culture, and what’s coming in the world in general. I have already visited experimental church services, psychedelic ceremonies, wellness centers, and group psychology practices that accomplish more than Peoplehood. These kinds of spaces are blossoming, and many of them are far more potent—deeper, more immersive, more magical, more culty, even more dangerous, even more holy.

Peoplehood is an unconvincing prototype, and when it’s gone it will neither be missed nor remembered. But contemporaries will learn from it, and learn from what I write here, and will become more potent. As much as I am encouraging more experimentation, I also insist that we examine these practices and places, because they are the churches of our time. Their moral, intellectual, and behavioral influence over us is great. The most successful will become part of our reality, and integral to our lives. What I am doing here is figuring out a shape of criticism and commentary and design that suits the medium: life itself.

Member discussion