Prototyping Social Forms of Care

I’m coming up on a year of researching health and wellness, and I’m starting to notice parallels to phenomena I studied in the crypto space. Much of what I’ve investigated over the last 7 years has been some kind of experimental organization or institutional prototype. In crypto, these were largely groups of strangers building software to manage financial resources and make collective decisions. Now I’m paying attention to organizations that center healing in some way, from virtual coaching retreats to community clinics.

One significant thing these organizations and social technologies share is that they all seek to create new social paradigms, to stand apart from legacy institutions of finance and care. My favorite people in crypto are those who want to leverage the technology for cultural change, emphasizing public goods and participatory governance. The community leaders, therapists, and founders who get in touch with me via Care Culture are similar: they see the broader cultural relevance of the models of care they’re experimenting with, and want to have a bigger impact on how health, spirituality, and community are integrated. They share a sense that the integration of these elements are key to healing social and civic life, and to the next generation of psychiatric practice.

Here is how I put the question being asked by all these parties: what role do therapists, coaches, healers, guides, clinicians, and other “helping professions” have to play in establishing new social forms—social forms which themselves heal, enliven, and strengthen the social fabric?

By researching how different people and communities answer this question, we may begin to understand the pattern languages and even design methodologies for these new institutions of care. Increasingly I see my role as encouraging these kinds of experiments. I want to help formalize and link these efforts together, building networks of learning between organizers.

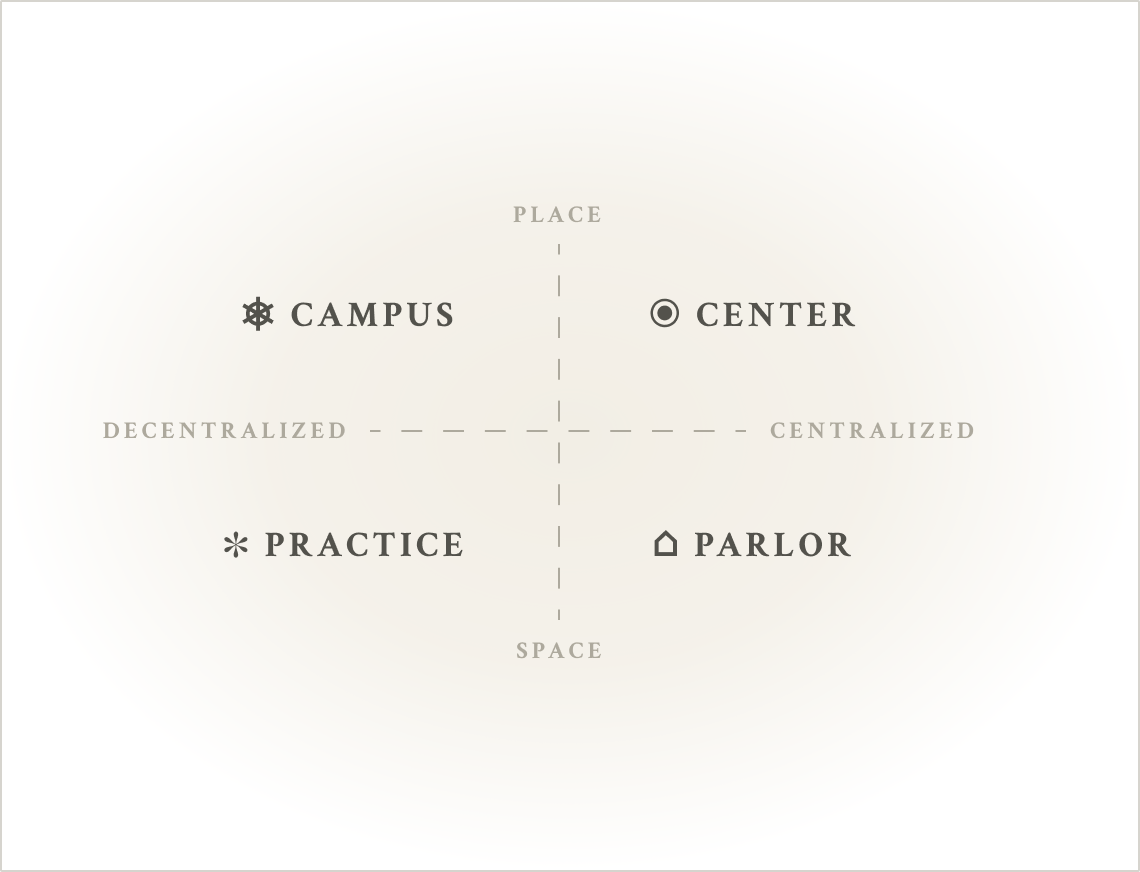

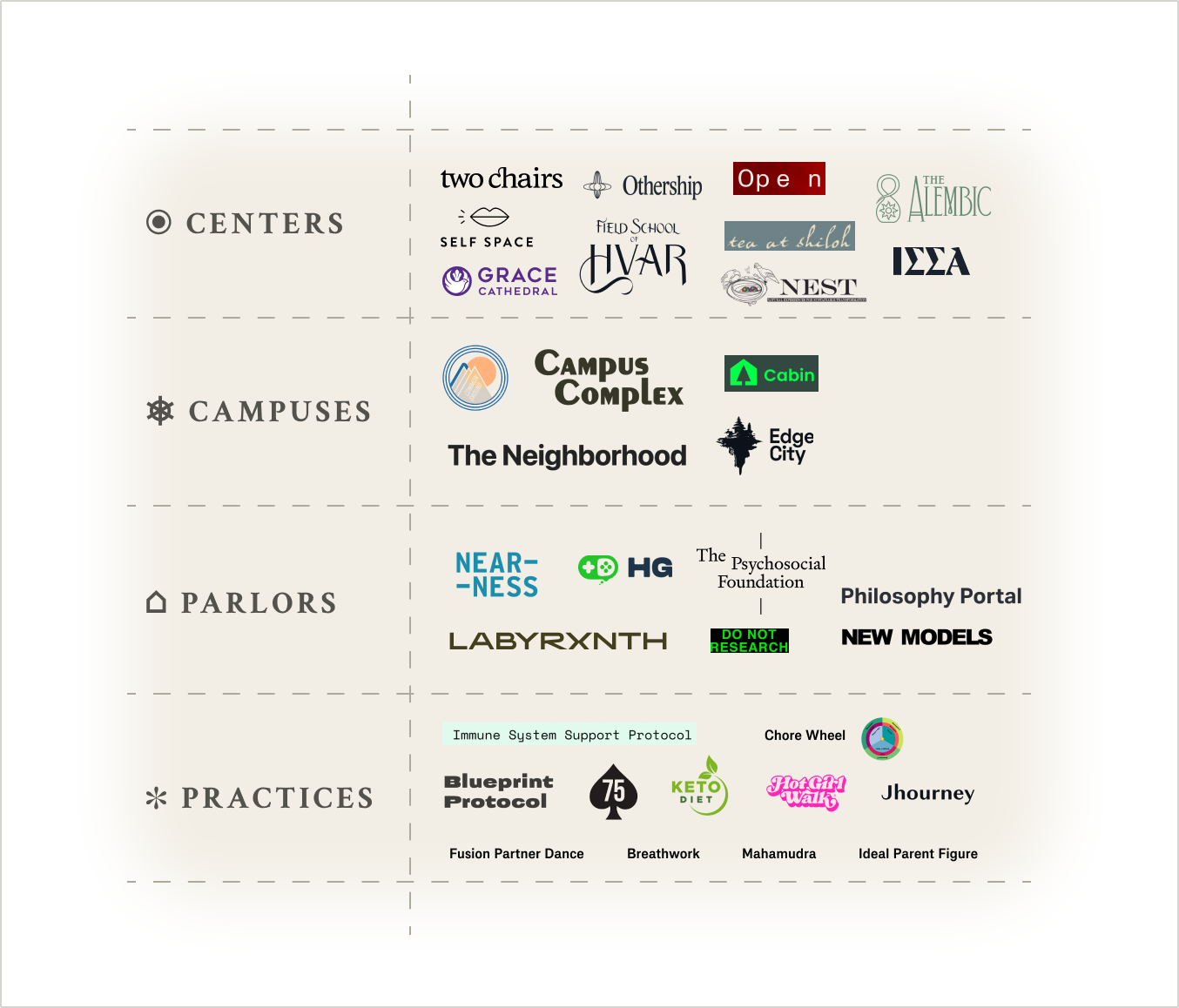

A first necessary step is to categorize some of the hybrid organizations I’ve been seeing. It won’t be an exhaustive list, but just one taxonomy that might be helpful. Across community and spiritual leaders, alternative psychology folks, educators, and innovative community organizers, I’ve found that institutional prototypes are combinations of these four categories of social form. ⦿ Centers are physical community spaces with a healing focus. ⎈ Campuses network together spaces in the existing built environment under a new identity. ⌂ Parlors are private spaces of digital discourse. ✽ Practices connect people across space and time through sustained embodied activity.

To briefly explain my terminology, “place” refers to things localized in the physical realm, while “space” refers to the distributed nature of activities conducted over the internet. Many of the experiments of the last decade, from cryptonetworks to digital academies, have been in “space.” But as I argued in my Body Futurism talk, the exhaustion of software means place is once again coming to the fore. I’ve been visiting a lot of IRL retreats, clinics, churches, and community centers with burgeoning energy. And some of the most exciting new social forms I’ve seen are placemaking initiatives that congregate digital communities in the physical realm.

As for “centralized” and “decentralized,” I use these terms in a value-neutral way. In my years working in crypto and hanging out in artist and activist circles, I’ve seen that many people automatically assign virtue to “decentralization.” But for my purposes here, decentralized social architectures are simply those that aim to distribute authority, power, and responsibility across multiple actors. By contrast, centralized social forms, whether spiritual communities or health centers, are simply those which have clear points of authority, hierarchy, and control.

“Social form” is the term I use to talk about all of these institutional prototypes. Social forms are structured architectures of behavior that determine the shape of social situations. The Brooklyn Public Library is an institution, but the public library itself is a social form. Social forms are the templates of social life: school classrooms, retreats, clinics, universities, art residencies, therapy sessions, mens and womens groups, camps, meditation centers, classes, salons, apprenticeships, sport clubs, fitness studios, and newfangled pop-up villages are just a sampling of the vast range of forms that make up our culture’s basic repertoire of social situations.

Why should new social forms play the pivotal role in cultural renewal, as opposed to institutional reform?

In recent years, technocratic centrists who identify with an “abundance and progress” agenda have made a compelling argument for increasing the speed and efficacy of existing institutions, through initiatives like improving NIH grant funding. Institutional reform is worthwhile and impactful, but challenging and capital-intensive. Many larger institutions have have become captured by rent-seeking bodies which have little incentive to change, like universities and for-profit hospitals encumbered by administrative bloat.

Geriatric and extractive institutions, however, are not the only areas of stagnation. Social forms themselves can themselves fall into disuse. Fraternal organizations and small-scale civic organizations in the US are two social forms indicative of this neglect: they played an important role in Tocqueville's America, but have little vitality today. In a report on civic associations, Lewis et. al describe how social media platforms have out-competed neighborhood associations, to be the “most representative layer of the governance stack.” In this media environment, additional financing isn’t sufficient to restore civic organizations to centrality in social life. Their way of operating, programming, communications, and how they recruit and retain members all need updates to suit today’s language and media environment. When people don’t see themselves in these organizations, they don’t join them. I suspect this lack of fit shows up in other social metrics, such as declining participation in civic life, being outside, and marriage rates, not to mention grand narratives about loneliness and meaning crises.

As I have argued elsewhere, social programs aimed at “solving the loneliness epidemic” are only good at directing capital towards organizations with familiar shapes. They are ineffective at identifying what formal innovations will make these organizations adaptive for the contmporary milieu, or discovering what new social forms might fill that role. I believe that on-the-ground experimentation, and capital allocation across the social and commercial sectors, should be directed at these goals.

It might be countered that some social forms don’t need an update. Aren’t churches lindy? This ignores the fact that many churches are experimenting with modern communications strategies and updated programming today. Grace Cathedral opens itself to yoga, sound baths, and social justice work, keeping its core as an Anglican community church but meeting a wider array of seekers where they are.

Experimentation with social forms is thus a different route to cultural renewal, one which is more open to ingenuity from a wider range of actors. Socially minded founders and designers, health professionals and practitioners, community builders, and small businesses can play a role in developing new templates for communal life that are better adapted to today’s cultural context. Where many existing interventions are couched in the pathological frameworks of “health” and “crisis,” prototyping novel ways to gather, learn, and heal is pragmatic and optimistic.

Let’s now look at four categories where such experimentation is taking place, and see how each is fostering different kinds of communion and care.

⦿ Centers

Ancestral Forms: Ashrams, Masonic Lodges, Monastic Infirmaries, Sento, Pueblo Kiva, the Temple of Apollo at Delphi

Modern Antecedents: Esalen Institute, Spirit Rock, Elks Club, YMCA

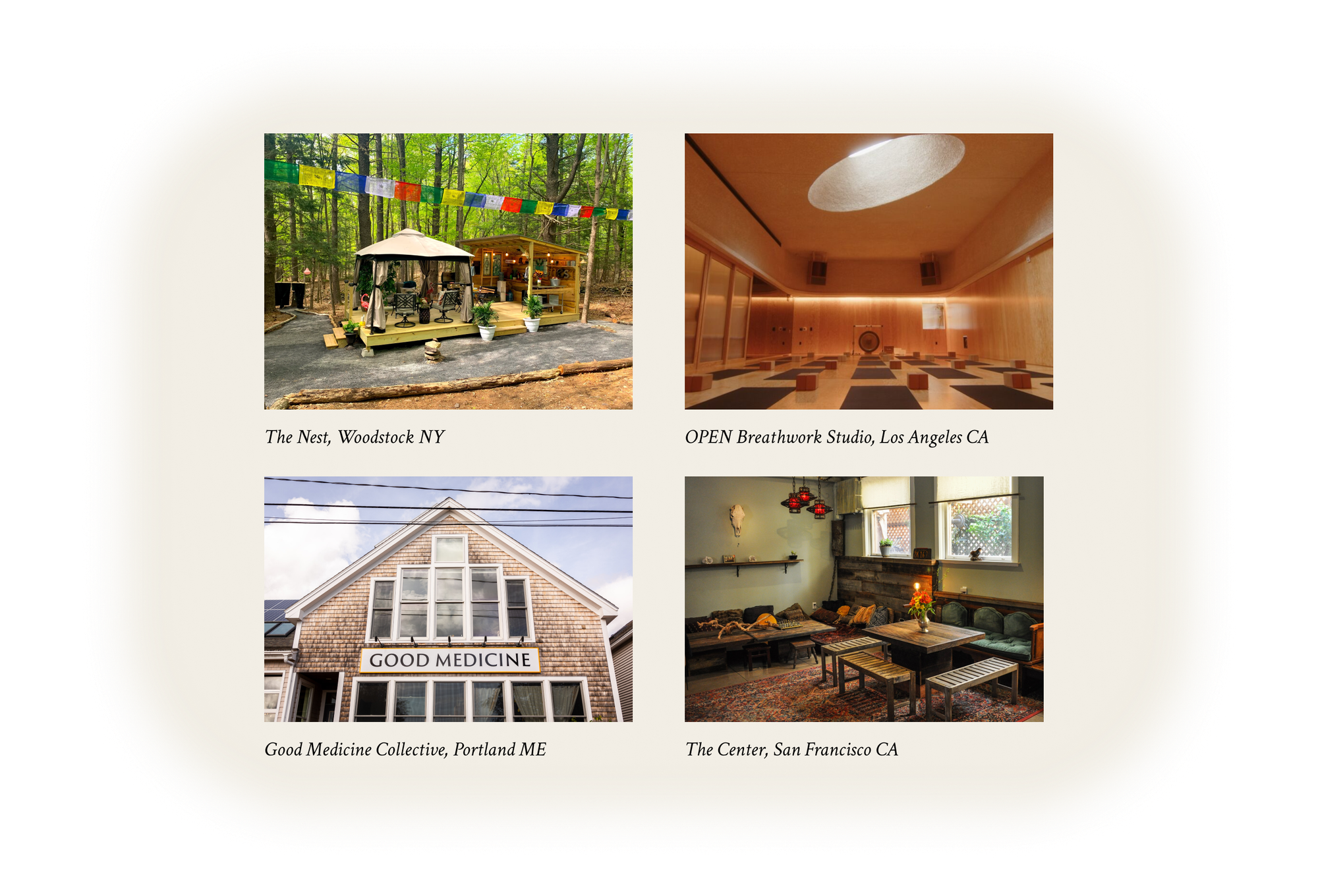

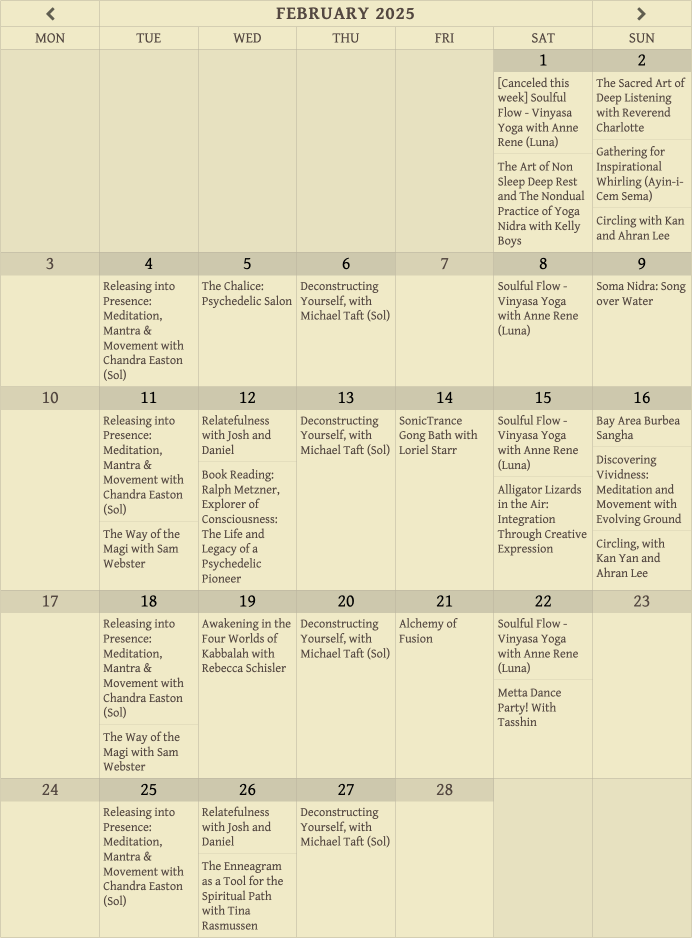

One emerging form of organization I’ve been looking at with Care Culture is a sort of hybrid between a church and a clinic and a school, which I simply refer to as a ⦿ Center. These organizations come in many shapes and sizes, with a spectrum of commercial interests and a vast array of spiritual or secular leanings. What all of these organizations feature is a physical place supporting community activities and gathering around some central vision of the good.

The Berkeley Alembic, an organization I frequent in the SF Bay Area, is a mindbody center where meditation, movement, and a range of spiritual teachings come together—an Esalen Institute in miniature. Peoplehood is a commercially driven endeavor with a flagship location in Chelsea, New York, focused a specific dialogue practice. Self Space in London is a small group practice employing a bunch of therapists, but with physical community space, classes, and book clubs. The Commons is a membership-supported community space in central San Francisco which describes itself as a modern town square. Temperance Alley Garden is a lush community garden and outdoor classroom on a vacant lot in Washington DC. ISSA is a school run by artists and activists under active construction on the Croatian island of Vis.

In all their forms, centers are physical places, which is why they can serve as effective community hubs. Even if they have an online component, like Self Space, and even if their physicality is temporary, such as Vibecamp or Fresh Air’s 30-day experimental retreat, it’s understood that the most meaningful expression of the community happens through physical gathering. Centers activate, invigorate, and integrate local life.

Likewise, some notion of the good life is inextricable from these places. The moral sensibility might be tied to a specific spiritual tradition, or it could be a more secular sense of what it means to live well, like OPEN’s notions of presence and “holistic longevity.” A center’s moral or spiritual vision is not always explicit, but even as an unstated vibe it’s a major part of what draws community together.

Relatedly, nearly every organization I’m looking at in this territory is concerned in some way with healing. “Healing” is core to the spiritual language of the West today; it doesn’t only refer to pain alleviation, but a movement towards wholeness in all dimensions of life. It’s a primary orientation for everything from secular wellness spas like Othership, to more traditional centers like Zen Mountain Monastery. Even new educational centers like Field School of Hvar or ISSA have a strong subtext of social healing and repair.

Finally, these orgs usually (but not always) have clear leadership, often vested in a person who exemplifies the moral or spiritual vision of the community. This person might have a priestly title like “Rinpoche,” or a secular one like “Founder” or “Doctor.” In other communities they may have the title “facilitator,” “chaplain,” “doula,” “professor,” or even “homemaker.”

The term “third place” has been popular to refer to physical community places. I think it’s time to retire this term. Just saying that these are non-work, non-home places gives no information about the kinds of places they are. This is why Starbucks was able to grift on “third space” so successfully. A Starbucks is not a community space, does not center healing, and has no vision of the good life—traits which clearly matter to the organizations popping up all around the nation. This movement doesn’t need a brand or special terminology to organize around.

That’s why I think ⦿ Center is an appropriate generic term for these newfangled hybrid organizations. Centers have plenty of precedent in older spiritual and clinical organizations, many of which already use “center” in the title. More importantly, wherever they are, they are always a center of social life. They’re often also a center of spiritual practice, in that something sacred or heightened can be sensed there. Even secular centers are at the center of a given community of practice. Something is alive here: a center is the locus of a lineage that extends backwards into the remembered past, and forward into the anticipated future of a living tradition. Centers are the heart space.

They are centers when they are in cities, because people want to live near them. They are centers because when they are deep in nature, because they make a place out of a location. They are centers because they draw people in from all around, and centers because they center communal concerns. They are centers because, as Christopher Alexander says, centers are the foundational unit of living structure, from which coherence, meaning, and wholeness unfold. And because being centered is an antidote to a placeless world.

⎈ Campuses

Ancestral Forms: Universities, Kumano Kōdō Pilgrimage, Free States and Pirate Republics

Modern Antecedents: Business Improvement Districts, Neighborhood Associations, Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone, TEDx, Burning Man & Regional Burns

The term ⎈ Campus alludes to the university campus: a well-landscaped environment with many departments and buildings, which together compose a vibrant, dynamic whole. Many of my favorite people to talk to right now are doing just this: building campuses out of diverse groups of people and places. These projects are placemaking endeavors. That is to say, they’re not new builds, but new senses of place. A campus is a sense of place that ties together physical spaces and infrastructure. A new sense of place can be supportive of many different purposes—learning, living, and perhaps healing. Let me give examples of each.

The “campus” nomenclature is inspired by a fellowship program I was involved in, run by Norm O’Hagan and Yatú Espinosa, called Campus Complex. I’ll quote from the project documentation:

The program turned a disconnected group of private offices and studios into a traversable network of learning environments for three builders, artists, and researchers. Each fellow received a passport, called a Learner Card, to our constellation of spaces and educators. Their mission was to use the tools and affordances of the Campus to further their educational endeavors.

We ran the fellowship for four weeks, during which fellows used resources from across the campus to build a project that advanced their learning. Interestingly, this turned the private offices and studios of our friends into Centers of a sort. They became embedded in a fabric of learning, moving beyond “work vs home” models of physical place. By asking yourself “where do I like to learn?” it’s easy to begin mapping your own personal campus of learning.

A second kind of campus is more suited for living. The Neighborhood SF is a project that aims to get a thousand people living within one square mile of one another in central San Francisco. This campus is composed of coliving houses and a couple permanent community centers. Jason Benn, the project’s founder, holds themed unconferences to bring together people who might be a good fit to be roommates, then acts as real estate broker, finding group housing for them in the neighborhood. As more people think of themselves as living in the The Neighborhood and meet at group houses and local centers, they experience more neighborly chance encounters.

This year I’ve written a few times about pop-up cities, which are similar to the Neighborhood but temporary. The idea of a pop-up city or village is to bring about a thousand to a place, turning existing infrastructure into a temporary community spaces and housing, lasting a month or more. I’ve visited three pop-up villages this year, in Honduras, Healdsburg, and Chiang Mai. These were organizationally complex projects that required a lot of energy and operational prowess to pull off. Organizers needed to find arrangements for temporary community centers, book out enough housing for a few hundred people, organize daily catered meals, and coordinate dozens of people to lead talks, tracks, and activities.

What are the features of this social form? Each of these campus projects uses digital technology to link spaces together, but directs peoples’ attention firmly into physical place. Freedom of movement is always possible. In campuses I’ve visited, diversity of wisdom is often emphasized. Unlike the more culturally coherent center and parlor, these have been big tent environments where many people can thrive.

The experiments I mentioned here are do not overtly address healing; they’re rather in the vein of civic projects. Yet in a way, they each foster a culture of care through their aspiration to repair the social fabric. Campus Complex did this by activating otherwise-private offices and studios as semipublic places of learning. The Neighborhood does this by devising new ways for people in an area to meet and recognize one another. As Jason says in one update, he runs into friends once every 40 minutes on average. In this way, campuses extend the personal healing work of individual centers to a higher layer of the social ecology.

⌂ Parlor

Ancestral Forms: Plato’s Academy, The Republic of Letters, Medieval Scriptoria, Coffeehouse Salon

Modern Antecedents: Talk Radio, The WELL, Internet Forums, Listservs, Second Life

Moving from physical place to digital space, the last few years has seen an explosion in various kinds of ⌂ Parlor. The heyday of the internet “town square” is definitively over, and these private club-like spaces have already become the de facto location for intellectual life online. ‘Parlor’ evokes parlor games, as well as also parlor chat—both appropriate nouns, given Discord chat servers, an evolution of gaming VoIP software, is the standard medium for today’s digital parlors. A parlor is a private digital space, often organized around an influencer, where a community gathers for focused discourse, knowledge-sharing, and intellectual development.

The basic shape of this social form is well-established. It’s a group chat attached to an influential blog, stream, or podcast. The typical home parlor is someone’s well-arranged living room; online, it is the well-arranged Discord, WhatsApp, or Telegram group. Channels are named with emojis and neatly ordered. Dead topics are closed and archived. Important discussions are preserved for posterity. Most importantly, someone plays the role of host, giving the discourse its primary inflection, while moderators enforce decorum.

From this foundation there’s lively experimentation in a dozen directions. Periodicals, miniature social networks, and new types of online school and clinic are just some of the social forms growing out of the parlor stem cell. The Discord channel of the New Models podcast is idea clearing-house for a large swath of designers and culture sector workers. Water & Music is a research collective that consistently publishes some of the best industry research on the music business. Other parlors are new kinds of philosophical academy, such as Philosophy Portal and Voicecraft.

I’m specifically interested in online groups which have an orientation toward care. HealthyGamer evolved from a Twitch stream into a whole community with a seres of guides, coaching, and courses for teens and parents. Hannah Zeavin’s Psychosocial Foundation recently launched a virtual clinical arm. Diagnosis and chronic health support groups take many forms, from Facebook groups to custom-designed web applications. Author and nondual teacher Andrew Holecek hosts an online community called Night Club, a sangha for lucid dreamers and dream yoga practitioners.

These parlors are centers of community life in the same way that physical Centers are, but online, and usually for delocalized communities. Temporalities differ; Labyrxnth and Nearness offer temporary, digitally-hosted retreats with focused presence, while classic chatrooms and forums let people have more of a come-and-go experience. Even as more internet communities search for physical common ground, private parlor networks will continue to play an important role in wayfinding and support, education and practice, and service provision across the landscape of care.

✽ Practice

Ancestral Forms: Tea Ceremony, Zen Meditation, Martial Arts, Yogic Traditions, Contra Dance, Dialectic

Modern Antecedents: Morning Pages, Authentic Movement, Nonviolent Communication, Psychotherapy, Keto Diet

When Jerusalem and the Second Temple were destroyed by Romans in 70 CE, Jewish life lost its central city and its system of sacrificial worship. Traditions and religious statutes that were previously passed down orally were compiled by necessity into the Halacha. The subsequent era was defined by diasporic communities of Jews, connected through Talmudic study, observance of the written Jewish law, and prayer in synagogues. These developments illustrate the basic principles of our last social form, ✽ Practice.

When we look at the history of healing, spiritual, and civic traditions, we find that at their heart are living practices: embodied ways of being that evolve through transmission and personal exploration within a community. One might ask why I situate these embodied social forms in “space” rather than “place.” I do so because of the unique way practices can transcend space and time. Think of Halacha, Brazillian Jiu Jitsu, and Japanese tea ceremony. Practitioners of each may come together, but they also may be distant in space and time. Yet the practice connects their bodies through the tacit knowledge they share. In this way, practices lean towards continuity across generations through the ongoing dialogue between form and sponteneaity, received wisdom and lived experience.

What makes something a practice, rather than just a habit or technique?

- Practices have lineage and community, even if informal. They are shared through relationships of disciplined mentorship and freeform peer learning.

- Practices develop over time through dedicated engagement, revealing deeper layers of subtelty and mastery. A meditator finds their natural sitting position and channels of open awareness. A somatic therapist learns to attune their interventions to each client’s nervous system. A skilled facilitator adapts the style of their teachers as they grow in expertise. Though practices might start with a fixed technique, through commitment and repetition they tend foster individual variation.

- Finally, practices do not just aim to transform behavior to some end, but contain within them meaningful ways of perceiving and being in the world.

Today we’re seeing a renaissance of practice-based approaches to healing and growth. Psychedelic integration coaching is a practice still in the early phases of professionalization. Somatic therapists and ecopsychologists are developing embodied practices for trauma resolution and connection to the physical world. Contemplative traditions and meditative secrets are being fused with new recent research to produce hybrid practices like yoga-based trauma care and breathwork for nervous system regulation. Video-based media social like TikTok and Instagram Reels have become powerful channels for popularizing practices that until recently were considered fringe.

Practices are not limited to physical and psychological healing of course. Many social forms are kinds of practice: fusion partner dance, group dialogues like Bohm Dialogue and Circling, restorative justice methods, artistic practices, and furthermore idiosyncratic things. The company Foster hosts great community writing circles. My friends Joe Edelman and Anne Selke have taught hundreds of people a delightful practice about understanding and living values. As all these examples demonstrate, practices alone encompass a vast range of social forms. Practices can be the heart of a community, or they can be mixed into other communities and social forms.

I want to touch briefly on “protocols,” an idea which has gained currency in tech-savvy wellness circles. In this context, protocols are standardized sets of rules or procedures, often designed to achieve specific outcomes across different contexts. Andrew Huberman’s sleep optimization routines and Grimhood’s recovery and detox plans are two examples. These protocols aim to structure an area of practice into something easily communicable and adoptable. They are standardized frameworks, making them clear starting points for beginners.

The broader connotations of “protocol” and “practice” illustrate an intrinsic tension in this social form: commitment versus play, obligation versus exploration. “Protocol” evokes the rigorous commitment one might make to a lineage, religious group, or community, whereas practice evokes the personal element of action, steady improvement, and exploratory development. Over-protocolizing can compromise the element of personal discovery and learning, while practices can become individualistic, devolving into dilettantism that goes nowhere. Clearly the term “protocol” has tapped into the technological zeitgeist. But I think both terms are good to keep in mind, for both designers and practitioners.

Not all new social forms fit into this taxonomy, but these categories already give us a lot to think about. For one, we can look at the different kinds of leadership required by each social form. What I’ve seen is that most centers are founded by charismatic individuals who naturally hold social gravity in their communities. They are great “fishers of men,” but less great at running an organization. Strong operators who can make centers sustainable and solvent are necessary complements to the gatherer’s skillset. As it currently stands this is a key talent gap.

Practices also often have a charismatic founder whose main job is to sacralize the practice. Compare Huberman, the science communicator, to Hübl, the mystic and trauma integration teacher. Both are charismatic, but Huberman mostly restricts himself to extolling the benefits of specific methods. Scientist leaders work well in the practice-protocol domain. Brene Brown, Richard Schwartz of IFS, Vitalik Buterin for Ethereum, are good analogues. Because of the non-localized nature of practice, these leaders focus on building strong distribution and marketing organizations, like Ethereum Foundation or the EMDR Institute.

Parlor people are well understood. My friend Kara calls streamers and podcasters “the intellectuals of the proletariat,” who “modulate the discourse and become representatives for their audiences’ will.” That about sums it up. These people mostly need to be prolific writers and unflappable talkers.

Campuses are by far the most logistically challenging of the forms we’ve covered. They require coordinating people and places into a shared texture, involving many centers and perhaps dozens of events. This demands the social skills of the charismatic founder persona and the operational gifts of an experienced producer. I’ve seen people with backgrounds in conference, festival, and hackathon organizing suceed here, but it’s ultimately a team sport.

There’s probably much more to extrapolate from the taxonomy, but I’ll leave it to readers to work out other interesting implications.

Return to Form

I want to conclude by coming back to the idea of form. I first got interested in form a few years ago when thinking about new forms of art being explored today. I wondered why art forms like sculpture and painting no longer capture the public’s imagination, why populist art forms were moving toward immersive simulations of altered states, and why the capital-A Art World had become interested in the "research-based practice" and the corporation as an art form. I was also influenced to think about form over many years of conversation with Nadia Asparouhova. For years, Nadia has been convinced that tech culture is in a formal deficit; the only shape of organization it will fund is startups. She wants to change that, so she started researching open source software production, and then later the history of philanthropy. I myself spent years exploring new forms of research institute with my previous organization, Other Internet.

My friend Chris Beiser says that social forms are a kind of capital that is essential to the structure of society and production. To put it a bit differently, the repertoire of forms dictates the kinds of lives that are available to us. These forms are forms of life. The organizations I am looking at are sincere meaning-making endeavors, post-lifestyle projects which are trying to ingrain themselves into culture at large. And that is why the analogy to art is so relevant. Art criticism today is mostly dead, but it’s worth writing a critical review about Peoplehood’s dialogue practices or pop-up cities. What I’m trying to do is figure out the shape of design, criticism, and commentary that suits the medium: the form of life itself.

So I think everyone working in health care innovation, or “spiritual innovation,” and certainly in policy, should be very interested in form. We should all be trying to understand the very shapes of these institutional prototypes, their formal properties, and what makes them successful and sustainable and what makes them fail. Like the founders and organizers of the projects I mentioned here, I am interested in different ways of life—ways of life that are not normal or accessible to most Americans today. Even the wealthiest Americans find it hard to embed themselves in networks and lifestyles of care and mutual support. It's actually the most disadvantaged, our poor and immigrant populations, whose churches and mutual aid networks most deeply express the ethos of community that more privileged Americans are now trying to recreate in the form of for-profit organizations. There is an irony and sadness to this. It seems unlikely to me that stuffing social aspirations (e.g. “solving the loneliness epidemic”) into commercial vehicles will fully address the core problem.

Identifying the formal similarities and differences of all these prototypes helps us understand the tradeoffs in the design space. Commercial versus voluntary, strong versus weak ties in communal life, charismatic versus leaderless, are just a few of the design decisions that need to be explored. Perhaps this clarifies further why formal experimentation, not just institutional reform, is required. With more experimentation, we can start to understand: what shapes are effective? What forms heal their maker? What does each uniquely need to work well? Which are suited to which kinds of capital structure and financing?

Working with form, of course, is a kind of play. And part of the point is for our social forms—the school, the church, the library, the hospital, the nursing home, the bank, the venture firm, the fraternity—to feel once again joyous and alive. So using this taxonomy as just the beginning, let’s play around and discover for ourselves.

With particular thanks to Mati Engel and Sam Wolf for substantive discussion and Andrew Jones for sparking the idea, my thanks to Jason Benn, Kati Devaney, Stedman Halliday, Norm O’Hagan & Yatú Espinosa, Chance McAllister, Chris Beiser, and Solon. Appreciation to Erik Davis and Jennifer Dumpert for leading a helpful discussion on practice. Credit is due to Casper Ter Kuile and Angie Thurston, whose famous “How We Gather” report itself provides the ancestral template for this post. And a deep thanks to Tyler Mincey and Kate McAndrew for their insights and supporting this work with a residency at Baukunst, itself a pioneering exploration in form.

Member discussion